2022 saw the pandemic-delayed Snowmass process confront the past, present, and future of particle physics. As the last papers trickle in for the year, we review Snowmass’s major developments and takeaways for particle theory.

It’s February 2022, and I am in an auditorium next to the beach in sunny Santa Barbara, listening to particle theory experts discuss their specialty. Each talk begins with roughly the same starting point: the Standard Model (SM) is incomplete. We know it is incomplete because, while its predictive capability is astonishingly impressive, it does not address a multitude of puzzles. These are the questions most familiar to any reader of popular physics: What is dark matter? What is dark energy? How can gravity be incorporated into the SM, which describes only 3 of the 4 known fundamental forces? How can we understand the origin of the SM’s structure — the values of its parameters, the hierarchy of its scales, and its “unnatural” constants that are calculated to be mysteriously small or far too large to be compatible with observation?

This compilation of questions is the reason that I, and all others in the room, are here. In the 80s, the business of particle discovery was booming. Eight new particles had been confirmed in the past two decades alone, cosmology was pivoting toward the recently developed inflationary paradigm, and supersymmetry (SUSY) was — as the lore goes — just around the corner. This flourish of progress and activity in the field had become too extensive for any collaboration or laboratory to address on its own. Meanwhile, links between theoretical developments, experimental proposals, and the flurry of results ballooned. The transition from the solitary 18th century tinkerer to the CERN summer student running an esoteric simulation for a research group was now complete: particle physics, as a field and community, had emerged.

It was only natural that the field sought a collective vision, or at minimum a notion of promising directions to pursue. In 1982, the American Physical Society’s Division of Particles and Fields organized Snowmass, a conference of a mere hundred participants that took place in a single room on a mountain in its namesake town of Snowmass, Colorado. Now, too large to be contained by its original location (although enthusiasm for organizing physics meetings at prominent ski locations abounds), Snowmass is both a conference and a multi-year process.

The depth and breadth of particle physics knowledge acquired in the last half-century is remarkable, yet a snapshot of the field today appears starkly different. The Higgs boson just celebrated its tenth “discovery birthday”, and while the completion of the Standard Model (SM) as we know it is no doubt a momentous achievement, no new fundamental particles have been found since, despite overwhelming evidence of the inevitability of new physics. Supersymmetry may still prove to be just around the corner at a next-generation collider…or orders of magnitude beyond our current experimental reach. Despite attention-grabbing headlines that herald the “death” of particle physics, there remains an abundance of questions ripe for exploration.

In light of this shift, the field is up against a challenge: how do we reconcile the disappointments of supersymmetry? Moreover, how can we make the case for the importance of fundamental physics research in an increasingly uncertain landscape?

The researchers are here at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP) at UC Santa Barbara to map out the “Theory Frontier” of the Snowmass process. The “frontiers” — subsections of the field focusing on a different approach of particle physics — have met over the past year to weave their own story of the last decade’s progress, burgeoning both questions and promising future trajectories. This past summer, thousands of particle physicists across the frontiers convened in Seattle, Washington to share, debate, and ponder questions and new directions. Now, these frontiers are collating their stories into an anthology.

Below are a few (theory) focal points in this astoundingly expansive picture.

Scattering Amplitudes

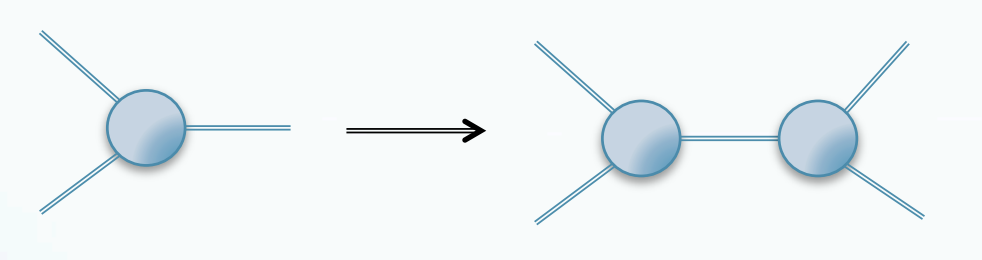

Quantum field theory (QFT) is the common language of particle physics. QFT provides a description of a particle system based on two fundamental tools: the Lagrangian and the path integral, which can both be wrapped up in the familiar diagrams of Richard Feynman. This approach, utilizing a visualization of incoming and outgoing scattering or decaying particles, has provided relief to many Ph.D. students over the past few generations due to its comparative ease of use. The diagrams are roughly divided into three parts: propagators (which tell us about the motion of a free particle), vertices (in which three or more particles interact), and loops (which describe the scenario in which the trajectory of two particles form a closed path). They contain both real, incoming particles, which are known as on-shell, as well as virtual, intermediate particles that cannot be measured, which are known as off-shell. To calculate a scattering amplitude — the probability of one or more particles interacting to form some specified final state — in this paradigm requires summing over all possibilities of what these virtual particles may be. This can prove not only cumbersome, but can also result in redundancies in our calculations.

Particle theory, however, is undergoing a paradigm shift. If we instead focus on the physical observable itself, the scattering amplitude, we can build more complicated diagrams from simpler ones in a recursive fashion. For example, we can imagine creating a 4-particle amplitude by gluing together two 3-particle amplitudes, as shown above. The process bypasses the intermediate, virtual particles and focuses only on computing on-shell states. This is not only a nice feature, but it can significantly reduce the problem at hand: calculating the scattering amplitude of 8 gluons with the Feynman approach requires computing more than a million Feynman diagrams, whereas the amplitudes method reduces the problem to a mere half-line.

In recent years, this program has seen renewed efforts, not only for its practical simplicity but also for its insights into the underlying concepts that shape particle interactions. The Lagrangian formalism organizes a theory based on the fields it contains and the symmetries those fields obey, with the rule of thumb that any term respecting the theory’s symmetries can be included in the Lagrangian. Further, these terms satisfy several general principles: Unitarity (the sum of the probabilities of each possible process in the theory adds to one, and time-evolves in a respecting manner), causality (an effect originates only from a cause that is contained in the effect’s backward light cone), and locality (observables that are localized at distinct regions in spacetime cannot affect one another). These are all reasonable axioms, but they must be explicitly baked into a theory that is represented in the Lagrangian formalism. Scattering amplitudes, in contrast, can reveal these principles without prior assumptions, signaling the unveiling of a more fundamental structure.

Recent research surrounding amplitudes concerns both diving deeper into this structure, as well as applying the results of the amplitudes program toward precision theory predictions. The past decade has seen a flurry of results from an idea known as bootstrapping, which takes the relationship between physics and mathematics and flips it on its head.

QFTs are typically built up from “bottom-up” by including terms in the Lagrangian based on which fields are present and which symmetries they obey. The bootstrapping methodology instead asks what the observable quantities are that result from a theory, and considers which underlying properties they must obey in order to be mathematically consistent. This process of elimination rules out a large swath of possibilities, significantly constraining the system and allowing us to, in some cases, guess our way to the answer.

This rich research program has plenty of directions to pursue. We can compute the scattering amplitudes of multi-loop diagrams in order to arrive at extremely precise SM predictions. We can probe their structure in the classical regime with the gravitational waves resulting from inspiraling stellar and black hole binaries. We can apply them to less understood regimes; for example, cosmological scattering amplitudes pose a unique challenge because they proceed in curved, rather than flat, space. Are there curved space analogues to the flat space amplitude structures? If so, what are they? What can we compute with them? Amplitudes are pushing forward our notion of what a QFT is. With them, we may be able to uncover the more fundamental frameworks that must underlie particle physics.

Computational Advances

Making theoretical predictions in the modern era has become incredibly computationally expensive. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and other accelerators produce over 100 terabytes of data per day while running, requiring not only intensive data filtering systems, but efficient computational methods to categorize and search for the signatures of particle collisions. Performing calculations in the quark sector — which relies on lattice gauge theory, in which spacetime is broken down into a discrete grid — also requires vast computational resources. And as simulations in astrophysics and cosmology balloon, so too does the supercomputing power needed to handle them.

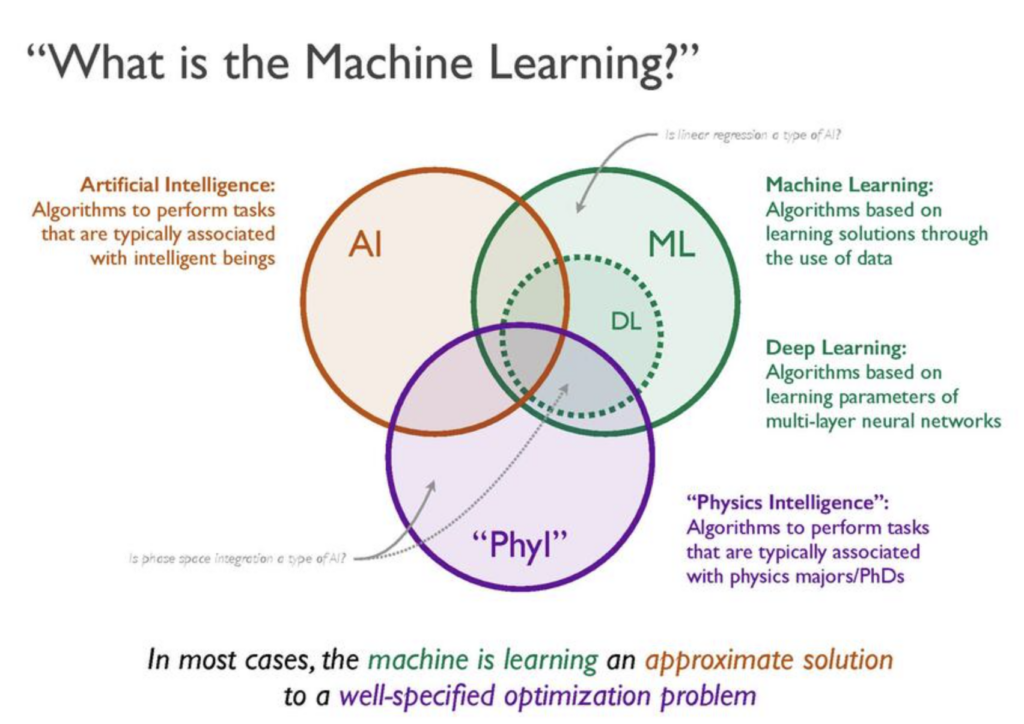

This challenge over the past decade has received a significant helping hand from the advent of machine learning — deep learning in particular. On the collider front, these techniques have been applied to the detection of anomalies — a deviation in the data from the SM “background” that may signal new physics — as well as the analysis of jets. These protocols can be trained on previously analyzed collider data and synthetic data to establish benchmarks and push computational efficiency much further. As the LHC enters its third operational run, it will be particularly focused on precision measurements as the increasing quantity of data allows for higher statistical certainty in our results. The growing list of anomalies — including the W mass measurement and the muon g-2 anomaly — will confront these increased statistics, allowing for possible confirmation or rejection of previous results. Our analyses have also grown more sophisticated; the showers of quarks and gluons that result from collisions of hadrons known as jets have proved to reveal substructure that opens up another avenue for comparison of data with an SM theory prediction.

The quark sector especially will benefit from the growing adoption of machine learning in particle physics. Analytical calculations in this sector are intractable due to strong coupling, so in practice calculations are built upon the use of lattice gauge theory. Increasingly precise calculations are dependent upon making this grid smaller and smaller and including more and more particles.

As physics continually benefits from the rapid development of machine learning and artificial intelligence, the field is up against a unique challenge. Machine learning algorithms can often be applied blindly, resulting in misunderstood outputs via a black box. The key in utilizing these techniques effectively is in asking the right questions, understanding what questions we are asking, and translating the physics appropriately to a machine learning context. This has its practical uses — in confidently identifying tasks for which automation is appropriate — but also opens up the possibility to formulate theoretical particle physics in a computational language. As we look toward the future, we can dream of the possibilities that could result from such a language: to what extent can we train a machine to learn physics itself? There is much work to be done before such questions can be answered, but the prospects are exciting nonetheless.

Cosmological Approaches

As the promise of SUSY is so far unfilled, the space of possible models is expansive, and anomalies pop up and disappear in our experiments, the field is yearning for a source of new data. While colliders have fueled significant progress in the past decades, a new horizon has formed with the launching of ultra-precise telescopes and gravitational wave detectors: probing the universe via cosmological data.

The use of observations of astrophysical and cosmological sources to tell us about particle physics is not new, — we’ve long hunted for supernovae and mapped the cosmic microwave background (CMB) — but nascent theory developments hold incredible potential for discovery. As of 2015, observations of gravitational waves guide insights into stellar and black hole binaries, with an eye toward a detection of a stochastic gravitational wave background originating from the period of exponential expansion known as inflation, which proceeded shortly after the big bang. The observation of black hole binaries in particular can provide valuable insights into the workings of gravity at the smallest of scales, when it enters the realm of quantum mechanics. The possibility of a stochastic gravitational wave background raises the promise of “seeing” the workings of the universe at earlier stages in its history than we’ve ever before been able to access, potentially even to the start of the universe itself.

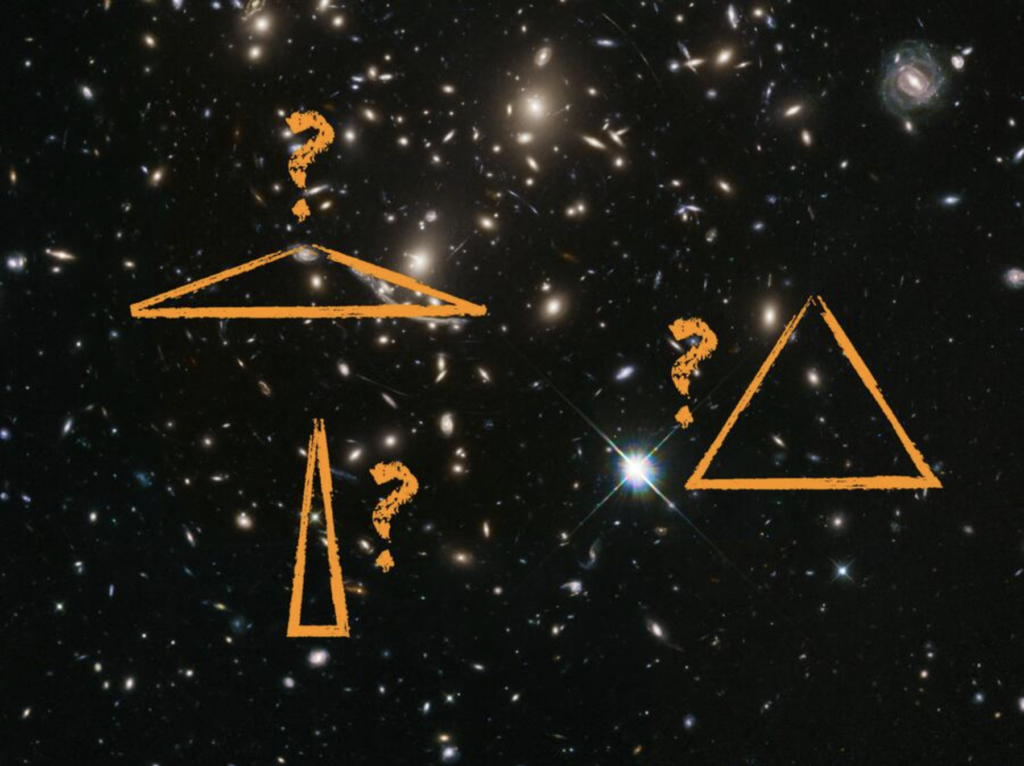

Inflation also lends itself to other applications within particle physics. Quantum fields at the beginning of the universe, in alignment with the uncertainty principle, predict tiny, statistical fluctuations. These initial spacetime curvature perturbations beget density perturbations in the distribution of matter which beget the temperature fluctuations visible in the cosmic microwave background (CMB). These fluctuations are observed to be distributed according to a Gaussian normal distribution, as of the latest CMB datasets. But tiny, primordial non-Gaussianities — processes that lead to a correlated pattern of fluctuations in the CMB and other datasets — are predicted for certain particle interactions during inflation. In particular, if particles interacting with the fields responsible for inflation acquire heavy masses during inflation, they could imprint a distinct, oscillating signature within these datasets. This would show up in our observables, such as the large-scale distribution of galaxies shown above, in the form of triangular (or higher-point polygonal) shapes signaling a non-Gaussian correlation. Currently, our probes of these non-Gaussianities are not precise enough to unveil such signatures, but planned and upcoming experiments may establish this new window into the workings of the early universe.

Finally, a section on the intersections of cosmology and particle physics would not be complete without mention of everyone’s favorite mystery: dark matter. A decade ago, the prime candidate for dark matter was the WIMP — the Weakly Interacting Massive Particle. This model was fairly simple, able to account for the 25% dark matter content of the universe we observe today, and remain in harmony with all other known cosmology. However, we’ve now probed a large swath of possible masses and cross-sections for the WIMP and come up short. The field’s focus has shifted to a different candidate for dark matter, the axion, which addresses both the dark matter mystery and a puzzle known as the strong CP problem simultaneously. While experiments to probe the axion parameter space are built, theorists are tasked with identifying well-motivated regions of this space — that is, possibilities for the mass and other parameters describing the axion that are plausible. The prospects include: theoretical motivation from calculations in string theory, considerations of the Peccei-Quinn symmetry underlying the notion of an axion, as well as various possible modes of production, including extreme astrophysical environments such as neutron stars and black holes.

Cosmological data has thus far been an important source not only into the history and evolution of the universe, but also of particle physics at high energy scales. As new telescopes and gravitational wave observatories are slated to come online within the next decade, expect this prolific field to continue to deliver alluring prospects for physics beyond the SM.

Neutrinos

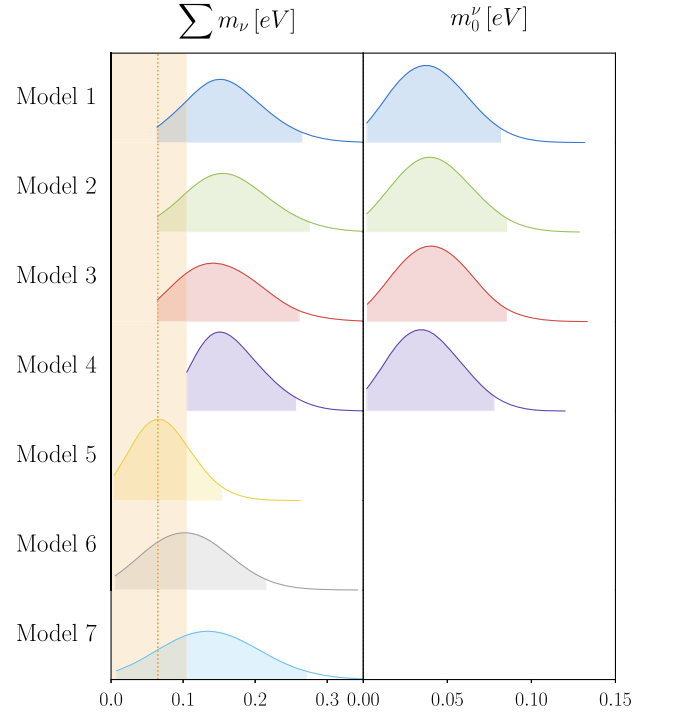

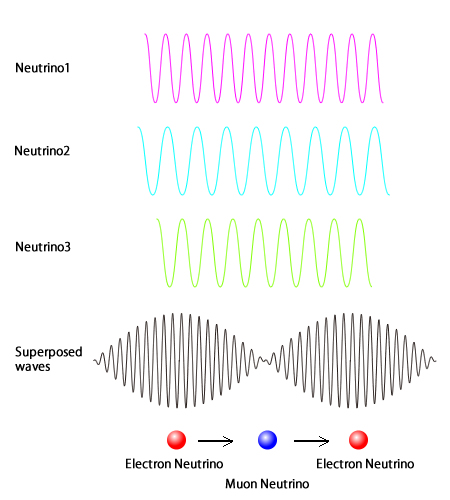

While the previous sections have highlighted new approaches to uncovering physics beyond the SM, there is a particular collection of particles that stand out in the spotlight. In the SM formulation, the three flavors of neutrinos are massless, just like the photon. Yet we know unequivocally from experiment that this is false. Neutrinos display a phenomenon known as neutrino mixing, in which one flavor of neutrino can turn into another flavor of neutrino as it propagates. This implies that at least two of the three neutrino flavors are in fact massive

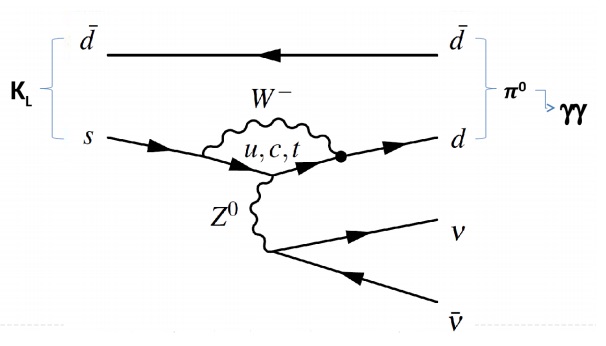

Investigating why neutrinos have mass — and where that mass comes from — is a central question in particle physics. Neutrinos are especially captivating because any observation of a neutrino mass mechanism is guaranteed to be a window to new physics. Further, neutrinos could be of central importance to several puzzles within the SM, including the MicroBooNE anomaly, the question of why there is more matter than antimatter in the observable universe, and the flavor puzzle, among others. The latter refers to an overall lack of understanding of the origin of flavor in the SM. Why do quarks come in six flavors, organized into three generations each consisting of one “up-type” quark with a +⅔ charge and one “down-type” quarks with a -⅓ charge? Why do leptons come in six flavors, with three pairs of one electron-like particle and one neutrino? What is the origin of the hierarchy of masses for both quarks and leptons? Of the SM’s 19 free parameters — which includes particle masses, coupling strengths, and others — 14 of them are associated with flavor.

The unequivocal evidence for neutrino mixing was the crown prize of the last few decades of neutrino physics research. Modern experiments are charged with detecting more subtle signs of new physics, through measurements of neutrino energy in colliders, ever more precise oscillation data, and the possibility for a heavy neutrino belonging to a fourth generation.

Experiment has a clear role to play; the upcoming Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) will produce neutrinos at Fermilab and observe them at Sanford Lab, South Dakota in order to accumulate data regarding long-distance neutrino oscillation. DUNE and other detectors will also turn their eye toward the sky in observations of neutrinos sourced by supernovae. There is also much room for theorists, both in developing models for neutrino mass-generation as well as influencing the future of neutrino experiment — short-distance neutrino oscillation experiments are a key proposal in the quest to address the MicroBooNE anomaly.

The field of neutrino physics is only growing. It is likely we’ll learn much more about the SM and beyond through these ghostly, mysterious particles in the coming decades.

Which Collider(s)?

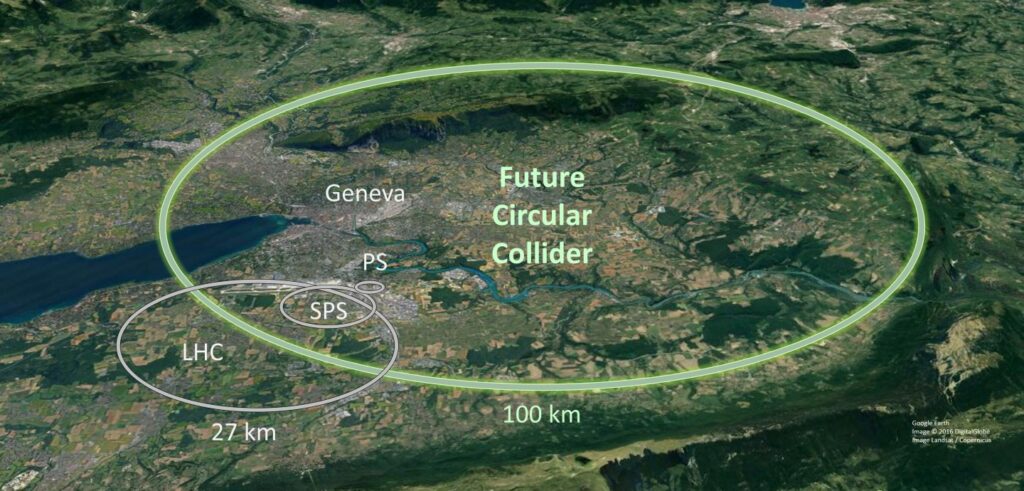

One looming question has formed an undercurrent through the entirety of the Snowmass process: What’s next after the LHC? In the past decade, propositions have been fleshed out in various stages, with the goal of satisfying some part of the lengthy wish list of questions a future collider would hope to probe.

The most well-known possible successor to the LHC is the Future Circular Collider (FCC), which is roughly a plan for a larger LHC, able to reach energies some 30 times that of its modern-day counterpart. An FCC that collides hadrons, as the LHC does, would extend the reach of our studies into the Higgs boson, other force-carrying gauge bosons, and dark matter searches. Its higher collision rate would enable studies of rare hadron decays and continue the trek into the realm of flavor physics searches. It would also enable our discovery of gauge bosons of new interactions — if they exist at those energies. This proposal, while captivating, has also met its fair share of skepticism, particularly because there is no singular particle physics goal it would be guaranteed to achieve. When the LHC was built, physicists were nearly certain that the Higgs boson would be found there — and it was. However, physicists were also somewhat confident in the prospect of finding SUSY at the LHC. Could supersymmetric particles be discovered at the FCC? Maybe, or maybe not.

A second plan exists for the FCC, in which it collides electrons and positrons instead of hadrons. This targets the electroweak sector of the SM, covering the properties of the Higgs, the W and Z bosons, and the heaviest quark (the top quark). Whereas hadrons are composite particles, and produce particle showers and jets upon collision, leptons are fundamental particles, and so have well-defined initial states. This allows for greater precision in measurements compared to hadron colliders, particularly in questions of the Higgs. Is the Higgs boson the only Higgs-like particle? Is it a composite particle? How does the origin of mass influence other key questions, such as the nature of dark matter? While unable to reach as high of energies as a hadron collider, an electron-positron collider is appealing due to its precision. This dichotomy epitomizes the choice between these two proposals for the FCC.

The options go beyond circular colliders. Linear colliders such as the International Linear Collider (ILC) and Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) are also on the table. While circular colliders are advantageous for their ability to accelerate particles over long distances and to keep un-collided particles in circulation for other experiments, they come with a particular disadvantage due to their shape. The acceleration of charged particles along a curved path results in synchrotron radiation — electromagnetic radiation that significantly reduces the energy available for each collision. For this reason, a circular accelerator is more suited to the collision of heavy particles — like the protons used in the LHC — than much lighter leptons. The lepton collisions within a linear accelerator would produce Higgs bosons at a high rate, allowing for deeper insight into the multitude of Higgs-related questions.

In the past few years, interest has grown for a different kind of lepton collider: a muon collider. Muons are, like electrons, fundamental particles, and therefore much cleaner in collisions than composite hadrons. They are also much more massive than electrons, which leads to a smaller proportion of energy being lost to synchrotron radiation in comparison to electron-positron colliders. This would allow for both high-precision measurements as well as high energies, making a muon collider an incredibly attractive candidate. The heavier mass of the muon, however, does bring with it a new set of technical challenges, particularly because the muon is not a stable particle and decays within a short timeframe.

As a multi-billion dollar project requiring the cooperation of numerous countries, getting a collider funded, constructed, and running is no easy feat. As collider proposals are put forth and debated, there is much at stake — a future collider will also determine the research programs and careers of many future students and professors. With that in mind, considerable care is necessary. Only one thing is certain: there will be something after the LHC.

Toward the Next Snowmass

The above snapshots are only a few of the myriad subtopics within particle theory; other notable ones include string theory, quantum information science, lattice gauge theory, and effective field theory. The full list of contributed papers can be found here.

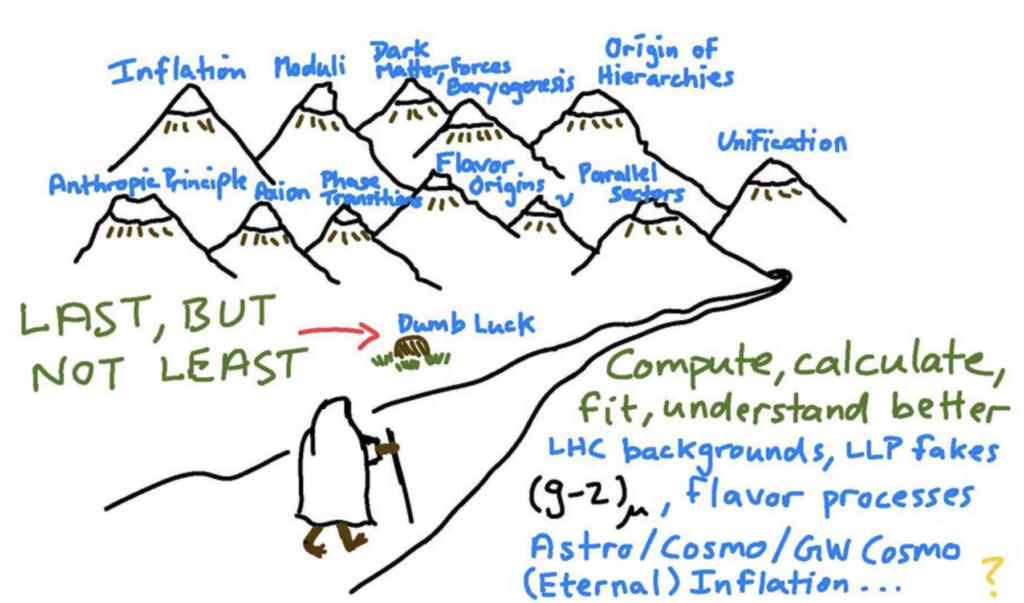

As the Snowmass process wraps up, the voice of particle theory has played and continues to play an influential role. Overall, progress in theory remains more accessible than in experiment — the number of possible models we’ve developed far outpaces the detectors we are able to build to investigate them. The theoretical physics community both guides the direction and targets of future experiments, and has plenty of room to make progress on the model-building front, including understanding quantum field theories at the deepest level and further uncovering the structures of amplitudes. A decade ago, SUSY at LHC-scales was at the prime objective in the hunt for an ultimate theory of physics. Now, new physics could be anywhere and everywhere; Snowmass is crucial to charting our path in an endless valley of questions. I look forward to the trails of the next decade.