The center of the galaxy is brighter than astrophysicists expected. Could this be the result of the self-annihilation of dark matter? Chris Karwin, a graduate student from the University of California, Irvine presents the Fermi collaboration’s analysis.

Editor’s note: this is a guest post by one of the students involved in the published result.

Authors: The Fermi-LAT Collaboration (ParticleBites blogger is a co-author)

Reference: 1511.02938, Astrophys.J. 819 (2016) no.1, 44

Introduction

Like other telescopes, the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope is a satellite that scans the sky collecting light. Unlike many telescopes, it searches for very high energy light: gamma-rays. The satellite’s main component is the Large Area Telescope (LAT). When this detector is hit with a high-energy gamma-ray, it measures the the energy and the direction in the sky from where it originated. The data provided by the LAT is an all-sky photon counts map:

In 2009, researchers noticed that there appeared to be an excess of gamma-rays coming from the galactic center. This excess is found by making a model of the known astrophysical gamma-ray sources and then comparing it to the data.

What makes the excess so interesting is that its features seem consistent with predictions from models of dark matter annihilation. Dark matter theory and simulations predict:

- The distribution of dark matter in space. The gamma rays coming from dark matter annihilation should follow this distribution, or spatial morphology.

- The particles to which dark matter directly annihilates. This gives a prediction for the expected energy spectrum of the gamma-rays.

Although a dark matter interpretation of the excess is a very exciting scenario that would tell us new things about particle physics, there are also other possible astrophysical explanations. For example, many physicists argue that the excess may be due to an unresolved population of milli-second pulsars. Another possible explanation is that it is simply due to the mis-modeling of the background. Regardless of the physical interpretation, the primary objective of the Fermi analysis is to characterize the excess.

The main systematic uncertainty of the experiment is our limited understanding of the backgrounds: the gamma rays produced by known astrophysical sources. In order to include this uncertainty in the analysis, four different background models are constructed. Although these models are methodically chosen so as to account for our lack of understanding, it should be noted that they do not necessarily span the entire range of possible error. For each of the background models, a gamma-ray excess is found. With the objective of characterizing the excess, additional components are then added to the model. Among the different components tested, it is found that the fit is most improved when dark matter is added. This is an indication that the signal may be coming from dark matter annihilation.

Analysis

This analysis is interested in the gamma rays coming from the galactic center. However, when looking towards the galactic center the telescope detects all of the gamma-rays coming from both the foreground and the background. The main challenge is to accurately model the gamma-rays coming from known astrophysical sources.

An overview of the analysis chain is as follows. The model of the observed region comes from performing a likelihood fit of the parameters for the known astrophysical sources. A likelihood fit is a statistical procedure that calculates the probability of observing the data given a set of parameters. In general there are two types of sources:

- Point sources such as known pulsars

- Diffuse sources due to the interaction of cosmic rays with the interstellar gas and radiation field

Parameters for these two types of sources are fit at the same time. One of the main uncertainties in the background is the cosmic ray source distribution. This is the number of cosmic ray sources as a function of distance from the center of the galaxy. It is believed that cosmic rays come from supernovae. However, the source distribution of supernova remnants is not well determined. Therefore, other tracers must be used. In this context a tracer refers to a measurement that can be made to infer the distribution of supernova remnants. This analysis uses both the distribution of OB stars and the distribution of pulsars as tracers. The former refers to OB associations, which are regions of O-type and B-type stars. These hot massive stars are progenitors of supernovae. In contrast to these progenitors, the distribution of pulsars is also used since pulsars are the end state of supernovae. These two extremes serve to encompass the uncertainty in the cosmic ray source distribution, although, as mentioned earlier, this uncertainty is by no means bracketing. Two of the four background model variants come from these distributions.

The information pertaining to the cosmic rays, gas, and radiation fields is input into a propagation code called GALPROP. This produces an all-sky gamma-ray intensity map for each of the physical processes that produce gamma-rays. These processes include the production of neutral pions due to the interaction of cosmic ray protons with the interstellar gas, which quickly decay into gamma-rays, cosmic ray electrons up-scattering low-energy photons of the radiation field via inverse Compton, and cosmic ray electrons interacting with the gas producing gamma-rays via Bremsstrahlung radiation.

The maps of all the processes are then tuned to the data. In general, tuning is a procedure by which the background models are optimized for the particular data set being used. This is done using a likelihood analysis. There are two different tuning procedures used for this analysis. One tunes the normalization of the maps, and the other tunes both the normalization and the extra degrees of freedom related to the gas emission interior to the solar circle. These two tuning procedures, performed for the the two cosmic ray source models, make up the four different background models.

Point source models are then determined for each background model, and the spectral parameters for both diffuse sources and point sources are simultaneously fit using a likelihood analysis.

Results and Conclusion

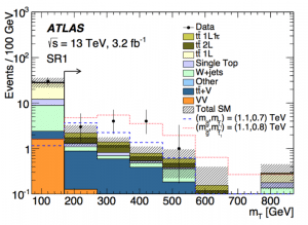

In the plot of the best fit dark matter spectra for the four background models, the hatching of each curve corresponds to the statistical uncertainty of the fit. The systematic uncertainty can be interpreted as the region enclosed by the four curves. Results from other analyses of the galactic center are overlaid on the plot. This result shows that the galactic center analysis performed by the Fermi collaboration allows a broad range of possible dark matter spectra.

The Fermi analysis has shown that within systematic uncertainties a gamma-ray excess coming from the galactic center is detected. In order to try to explain this excess additional components were added to the model. Among the additional components tested it was found that the fit is most improved with that addition of a dark matter component. However, this does not establish that a dark matter signal has been detected. There is still a good chance that the excess can be due to something else, such as an unresolved population of millisecond pulsars or mis-modeling of the background. Further work must be done to better understand the background and better characterize the excess. Nevertheless, it remains an exciting prospect that the gamma-ray excess could be a signal of dark matter.

Background reading on dark matter and indirect detection:

- TASI 2012 Lectures on Astrophysical Probes of Dark Matter, Stefano Profumo

- A History of Dark Matter, Gianfranco Bertone, Dan Hooper

- Lectures on Dark Matter Physics, Mariangela Lisanti